A Tribute to and Remembrance of My Father

The Baseball Career of Albert Michael Nozzi

My father -- Albert Michael Nozzi -- was born on July 10, 1931 in Dunmore, Lackawanna County, Pennsylvania. You were the son of Domenick Nozzi and Domenica Lalli.

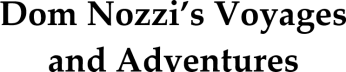

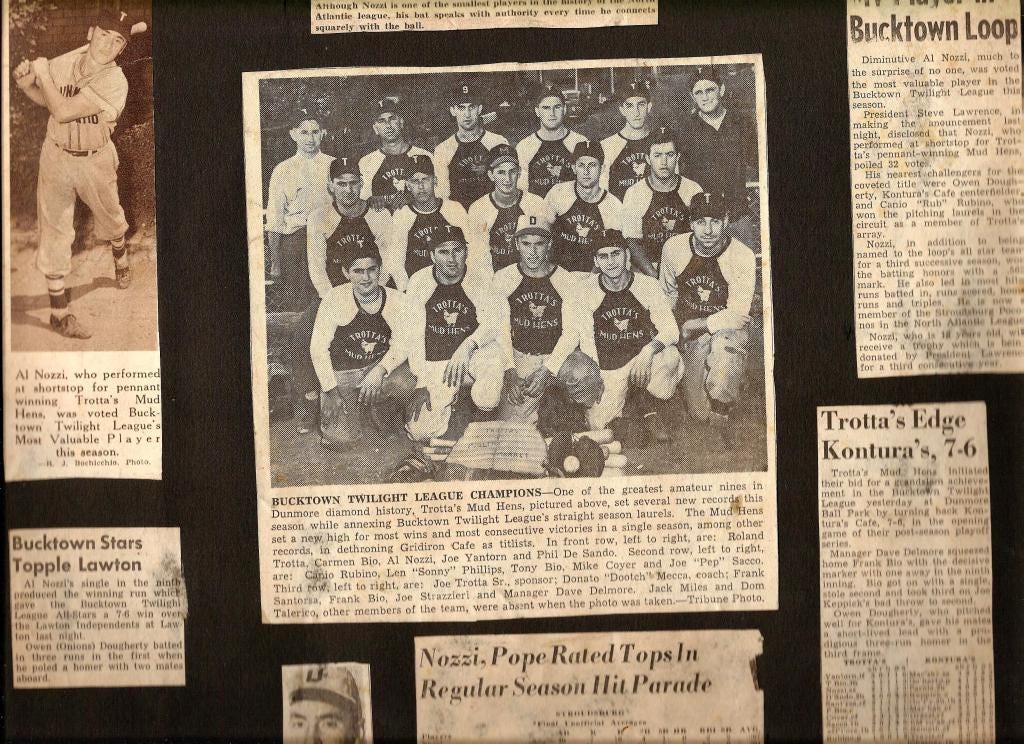

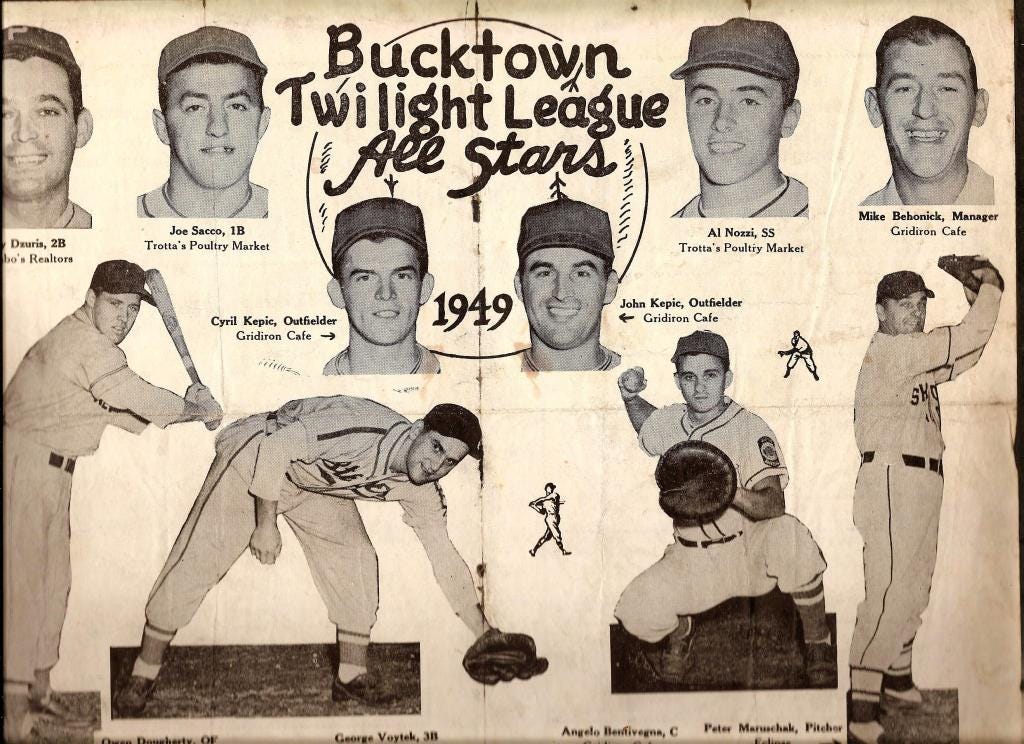

He played shortstop for Perry’s Truckers and Trotta’s (Produce Market) Mud Hens in the Bucktown Twi-light League, and was the leading hitter in the league.

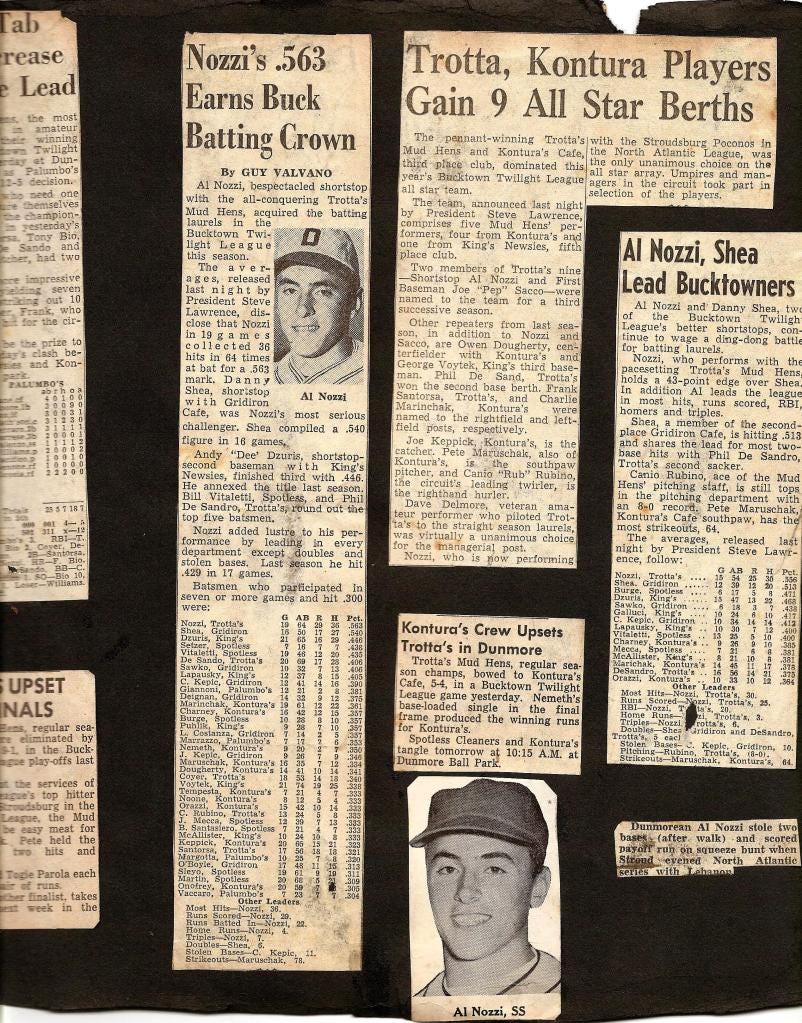

For three straight years (1948-1950), he was voted the Most Valuable Player in the League, and was placed on the All-Star team for those three years as well.

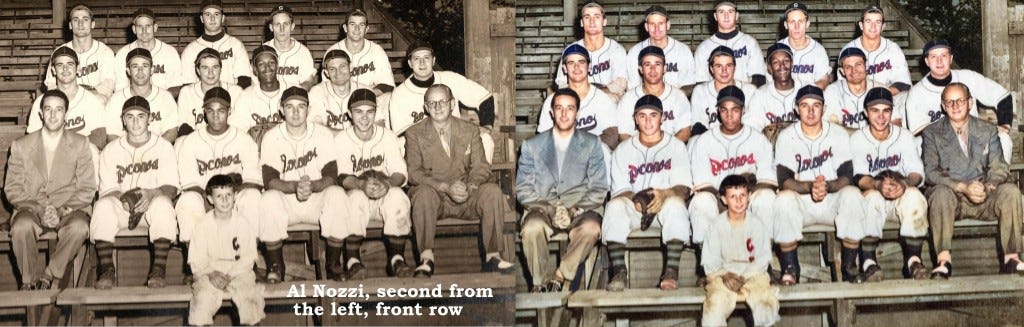

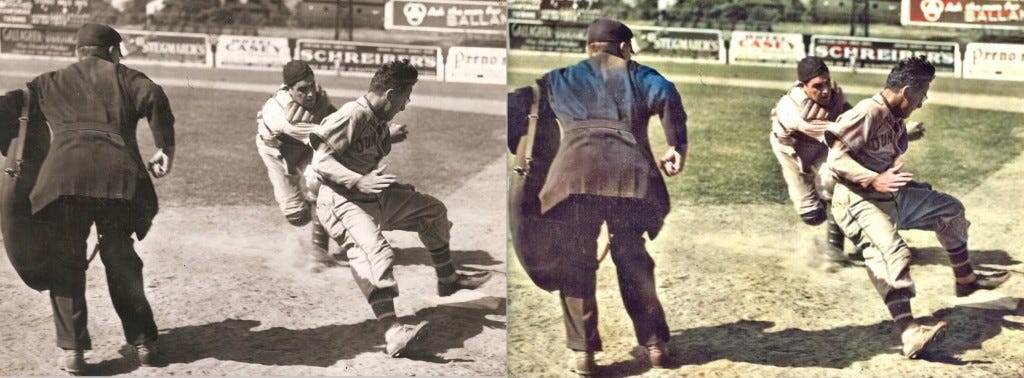

Al was signed by the Stroudsburg Poconos in the North Atlantic League and played for them in 1950 after leading the Bucktown League in hitting percentage, number of hits, runs batted in, runs scored, home runs, and triples.

The Stroudsburg Poconos, located in Stroudsburg, PA, was a minor league baseball team in the North Atlantic League from 1946 to 1950. Frank Radler was the manager. They were affiliated with the New York Yankees in 1947 and the Cleveland Indians in 1949.

Frank J. Radler (born c. 1920) was a minor league baseball player and manager who led two teams to league championships in the 1940s and 1950s.

A pitcher, Radler played in the minor leagues from 1937 to 1940, from 1943 to 1946 and from 1948 to 1952. He went 151-92 in his 13-year career, winning at least 20 games three times. In 1950, with the Stroudsburg Poconos, he went 21-3 with a 1.82 ERA in 35 games. In 1949, he posted a 1.59 ERA and in 1948, he went 20-8 with a 2.18 ERA.

He managed the Poconos from 1948 to 1950, leading them to a league championship victory in 1949 and a trip to the league finals in 1950.

The Poconos played their home games at Gordon Gifels Field. Their 1949 team was considered one of the top 100 minor league teams in the history of baseball. They went 101-36 that year. Following the 1950 season, the North Atlantic League folded and the Stroudsburg Poconos did as well.

In one game, Radler paid Al the ultimate compliment by letting Al pinch-hit for the Poconos against a left-handed pitcher. Managers almost never have a left-handed batter face a left-handed pitcher because it is so difficult for left-handed batters to bat against left-handed pitchers.

Al, a left-handed batter, rewarded his manager’s confidence in him when he lined a shot off the right field wall for a double against the lefty pitcher. The manager was quite impressed, and told Al at the end of the season that he believed Al could hit the higher level “A” League pitching.

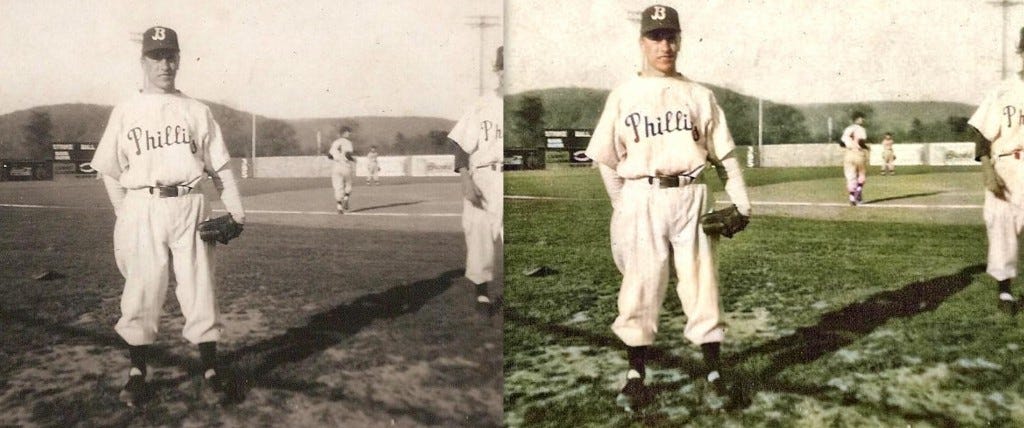

While with the Poconos, Al attracted the attention of a scout for the Philadelphia Phillies professional baseball team. The scout asked Al how tall his mother was. The scout wanted to get an idea of whether Al would ever grow taller, as he was quite short at the time (Al’s mother happened to be very short).

Al was infuriated by the question and resented the fact that the scout (and, earlier, his high school football coach) thought he was too short to play against larger players. Al felt like telling the scout that he could knock the scout on his butt.

The encounter occurred because there was a Donato restaurant in Dunmore, PA, and the West Scranton coach and part of the family owning the restaurant — Sammy Donato — decided to take Al to Stroudsburg to try out with the Class “D” professional baseball team.

Despite the “height of your mom” question from the scout, Al was immediately signed by the Phillies to play for their Bradford Phillies farm club (based in Bradford, PA) in the Pennsylvania-Ontario-New York League (the Class D PONY League), and played for them in 1951. Frank McCormick was the manager of the team.

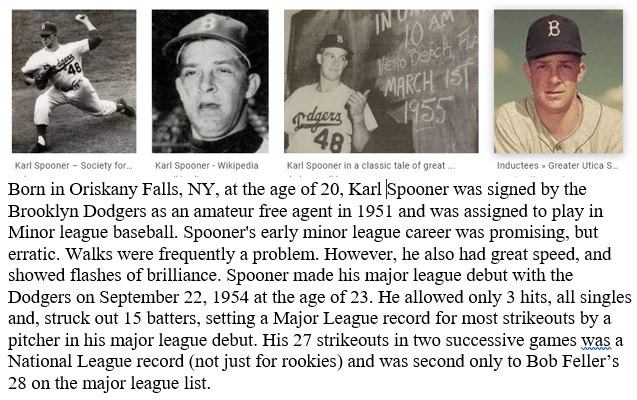

Al ended up batting against two pitchers that made it to Major League Baseball: Karl Spooner and Ted Abernathy. One day during the 1951 season, while playing in the PONY League, Al suffered an injury when he “threw his arm out,” which meant that he only faced Spooner in one game.

In that game, Spooner struck out Al three times. Al considered Spooner to be “Sneaky Fast.” Spooner, who threw a blazing 96 mile-per-hour fast ball, was the fastest pitcher Al ever faced. Al was released from the team due to the arm injury.

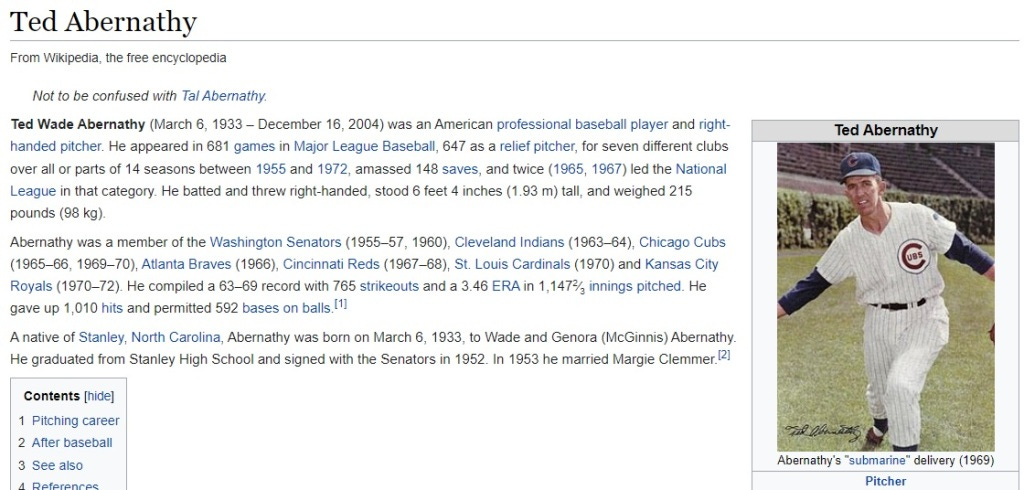

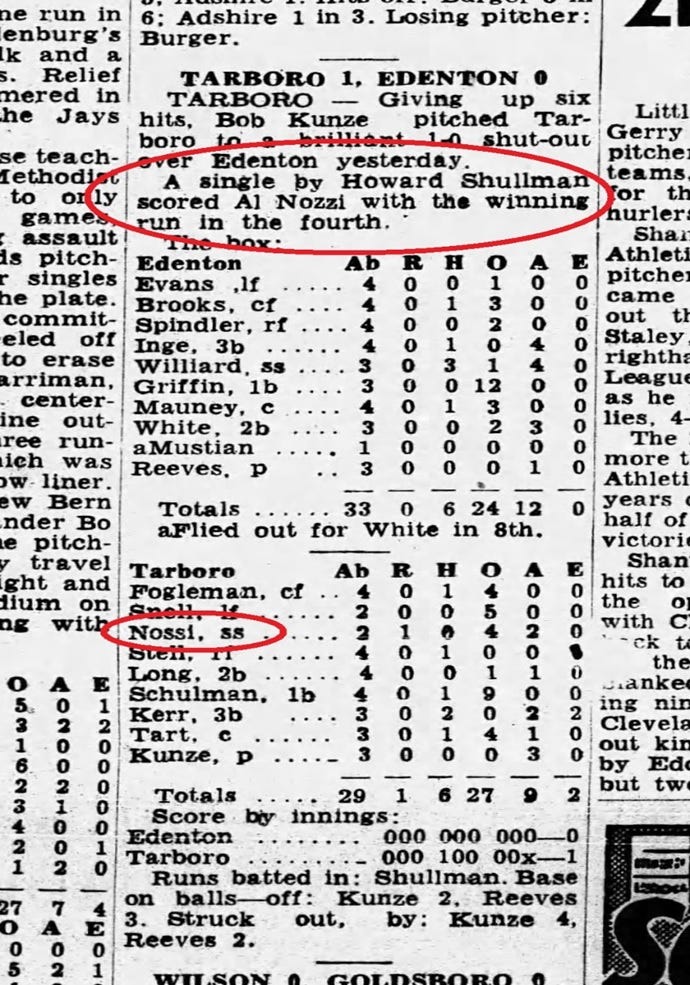

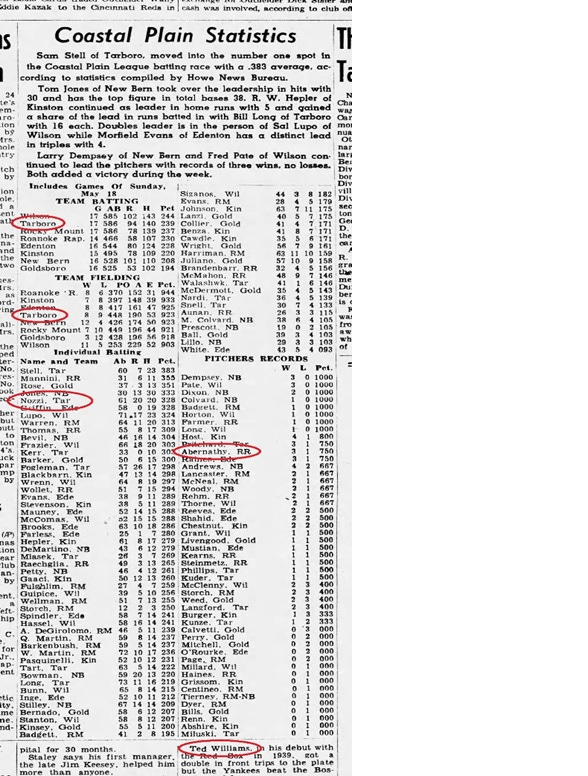

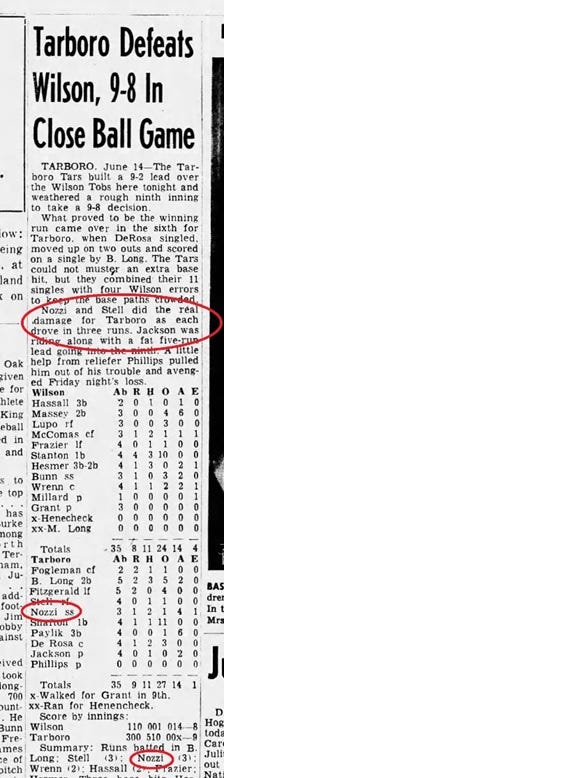

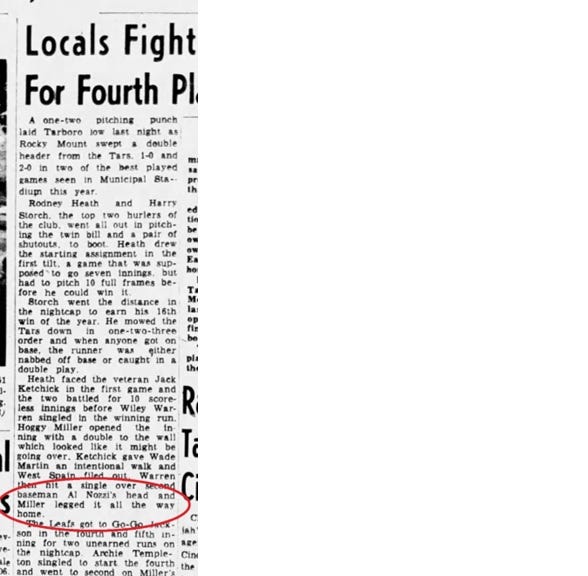

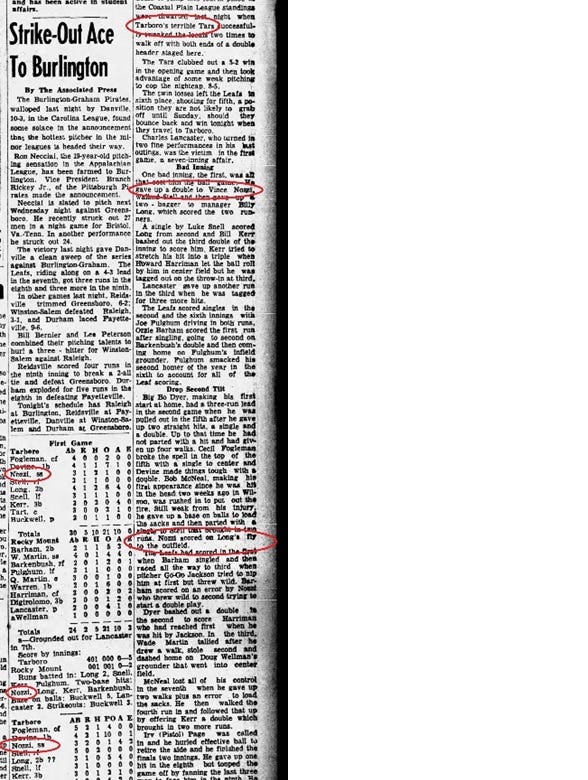

When Al batted against Ted Abernathy, he was facing a “side-arm” pitcher (almost an under-armer). Abernathy averaged 13 to 14 strikeouts a game against Al’s Tarboro Tars team in the Coastal Plain League (based in North Carolina) in 1952. Abernathy was almost unhittable when he faced the right-handed hitters for Tarboro.

Al, however, was quite successful against Abernathy — batting better than .350 against him. “I owned him,” Al said. Abernathy never struck out Al. It would be Al’s only full season of playing professional baseball. Billy Long was the manager of the Al’s Tarboro Tars at the time.

At the end of that 1952 season, Al was then scheduled to play in spring training with the Scranton Red Sox (in the higher-level “A” League) in 1953 in Winter Haven, Florida, but he was drafted into the Army to fight in the Korean War. Being drafted cut short Al’s promising baseball career.

He was offered a shot at playing for a Pro League (“C” or “D” League) team when he got out of the Service at the end of the 1954 season for the upcoming 1955 season. However, Al turned this offer down because he said he was tired of playing “D” League baseball. It is likely that had he not been drafted to serve in the war, he would have played professional baseball for the Phillies.

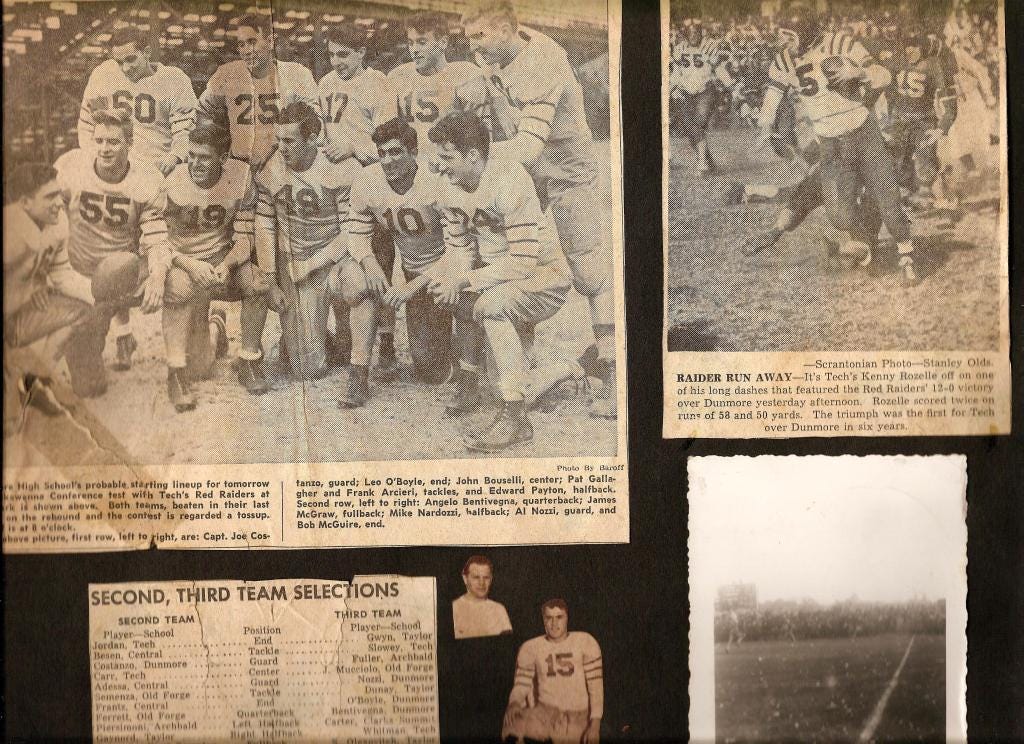

Many times, over the years, my father would express deep regret over an incident when, in high school, he was playing guard on the offensive line for the Dunmore Bucks high school football team (he also drop-kicked extra points for the team). On one particular play, a scout for East Stroudsburg University (the Warriors) in Pennsylvania noticed that my father was outrunning the running back down the field on a running play. The scout asked my father to consider playing quarterback for East Stroudsburg. He turned down the offer (because he wanted to be done with school). And for the rest of his life, my father painfully described to me how he still kicks himself for turning down the scout’s offer.

In Appreciation for My Father and Fatherhood

Dear Dad,

Thank you for being strong, heroic, masculine, protective, generous, dependable, supportive, disciplinary, patient, forgiving, wise, sympathetic, loving, helpful, instructive, insightful, and trusting.

I will always be grateful for the essential role you played in raising your children. For being able to instill in your children…

• leadership

• physical and emotional strength

• responsibility and accountability

• masculinity in your sons and femininity in your daughters

• the ability to be assertive in what we know and believe

• financial and other forms of self-control

• respect

• courage

• resilience and fortitude

• accountability

• a sense of adventure

• competitiveness and having a work ethic

• a desire to engage in a lifetime of self-learning and self-improvement

• a willingness to take on challenges rather than running from them

You taught me how to play baseball, how to play football, how to play bocce, how to play euchre, and how to wrestle (you would hold me and your other children on the floor and give us a “shave” by rubbing your facial stubble against our faces). You taught me I should never give up. You were a loving husband and father. You would, for example, change shifts when you worked at Xerox to spend more time with your wife and children. You tried – unsuccessfully – to teach me how to play guitar and drop kick a football. You taught me how to swing a hammer, shovel snow, and paint a house. You taught me to speak up when I disagreed with something. You taught me to enjoy reading. You taught me how to be an evangelist for my passionately held beliefs. You taught me how to care for the natural environment and be a conservationist. You taught me to enjoy the music of Jimmie Rodgers and how to yodel. You taught me how to ask questions if I did not know. You never missed an opportunity to ask me if I had ever smelled anything as heavenly as a peach. You taught me how to ride a bicycle and drive a car. You taught me the importance of getting an education and finding a job that I enjoyed (rather than just a high-paying job). You taught me how to fish and camp and build a campfire. You taught me the joys of eating soft ice cream (what you called “custard”). You taught me to enjoy reading a newspaper. You taught me how I should be proud to be myself and not just follow the crowd. You taught me the need to kiss my significant other each day, and to regularly enjoy wine. You taught me the importance of travel (by driving your family all over the nation for camping vacations), which gave me the courage to travel regularly on my own, and to pull up the stakes to seek to live in a better place. You taught me the importance of working hard. And you taught me how to be a kind, loving companion for my chosen life partner.

I feel extremely fortunate to have grown up in a time when it was more likely that you would possess such fathering skills, and worry about the decline in such skills (including a decline in the admiration for such skills) in contemporary society.

Thank you, Albert Michael Nozzi – my father, for being a wonderful, loving husband for 63 years to my mother -- your wife -- Sara Nozzi. She was exceptionally fortunate to have you as her life partner. And thank you for raising me and your other children so well. We could not have been the happy, successful adults we have become without you as our father.

You turned 91 years old on July 10th, 2022. As of September 26, 2022 – the day you died -- you had fathered six children who have produced for you nine grandchildren and four great-grandchildren. Happy Father's Day and Happy Birthday, Dad! I love you and am very proud of you. As a father and as a man.

Words cannot express how much I will miss you and how grateful I am for your being my father. I hope I have lived a life that made you proud of me.

Because you will always live in my heart and the heart of others, you will never truly die.

Your Proud Son Dominic

An interesting aside: Early in my career as a town planner, I was fortunate to read The Death and Life of Great American Cities by Jane Jacobs. Her influential book instilled in me a lifelong passion for urban design. Jacobs, like my father, was born in Dunmore Pennsylvania.

Cut Short but a Cut Above the Rest

As I noted above, while my father’s quite promising baseball career was cut short by the Korean War, and a scout for the Philadelphia Phillies major league baseball team worried he might be too short, my father was clearly a cut above the rest.

Having been an all-star baseball player for a number of years – stellar enough to have attracted the attention of major league baseball – my father was an exceptional athlete.

But he was more than that. He was an exceptional father, as my tribute to him illustrates above.

Many times, while I was growing up, my father would bitterly tell me about how he was often told he was too small in size to be a good athlete in baseball or football. Newspapers would refer to him as a “little bespectacled guy.”

He therefore was particularly sensitive when he heard me complain that I could not hope to compete against other players in sports because they were so much bigger. He would loudly tell me that “the bigger they are, Dom, the harder they fall!” And that “the only thing that stands in the way of Dom Nozzi is Dom Nozzi.”

My father taught me to run the bases, how to slide into a base, and how to swing a baseball bat like he did, which was left-handed.

Normally, a right-handed person such as my father and I would bat right-handed. In the reverse of batting right-handed, a left-handed batter holds a bat so that the left hand is above the right hand, and the right shoulder would be in front in a batting stance. This gave both my father and me an advantage when swinging a baseball bat, because when one swings a bat (or a tennis racket), the backhand (despite conventional wisdom) is stronger than the forehand, and since my father and I are right-handed, our strong and more coordinated arm is used for the stronger backhand in baseball, tennis, and hockey.

Since left-handed batters are between the catcher and first base, my father pointed out that batting left-handed also meant that I could reach first base faster when hitting, since first base is closer to a left-handed hitter than a right-handed hitter. A third advantage of batting left-handed is that nearly all pitchers are right-handed, and it is much easier for a left-handed hitter to get a hit against a right-handed pitcher than it is for such a pitcher against a right-handed batter (a ball thrown by a right-handed pitcher is more difficult for right-handed batters because the ball breaks away from the right-handed batter).

The “drag bunt” was a technique my father taught me because this form of hitting was only available to a left-handed hitter. Yet another benefit to being a lefty hitter.

According to my father, professional baseball players today are spoiled crybabies when they commonly charge the pitcher’s mound and throw punches at a pitcher who has thrown a “brush back” fastball at the batter (a pitch thrown at the batter to intimidate him and force him to back away from the plate).

Back in his day, he would tell me, this was a normal, expected part of the game. Indeed, my father enjoyed telling me about how a pitcher once threw a fastball at my father’s head. On the very next pitch, my father would say with a glint in his eye, he hit a screaming line drive that nearly took the pitcher’s head off. That’s how to respond to a “back off” pitch, my dad pointed out.

A common baseball warm-up that my father taught me was “pepper.” Pepper is a common pre-game exercise where one player uses a “fungo” bat to hit brisk grounders and line drives to a group of fielders who are standing about 20 feet away. The fielders throw to the batter, who uses a short, light swing to hit the ball on the ground back towards the fielders. The fielders field the ground balls and continue tossing the ball to the batter. This exercise keeps the fielders and batter alert, warms them up for playing a game, and helps to develop quickness and good hand-eye coordination.

My father worked with me for long hours to teach me to keep my eye on the ball while swinging, and to swing our bat level (parallel) with the ground. He taught me how to stand in the batter’s box (our foot closest to the pitcher should be slightly closer to the plate than our back foot). And how to step slightly toward the pitch when swinging (instead of stepping back from it).

He also told me again and again to keep our eye on the ball to field grounders on defense (and to stay down and keep myself square to the ball). His instructions for fielding fly balls also started by insisting that I keep my eye on the ball, and that for both grounders and fly balls I should use both hands. He warned me that show-offs — “hot dogs,” he called them — who catch with one hand often drop balls. When having us practice catching (“shagging”) fly balls in our backyard, he would hit me fly balls and yell things like “This is for a double chocolate sundae!!” to give me more incentive to catch the ball. He never did buy me a sundae after those sessions, now that I think about it…

As an aside, I currently live in Greenville South Carolina, which has its own "higher-level" A League baseball team. That team plays against the Asheville North Carolina team. Since my father played for the Tarboro Tars (just down the road from Asheville), there is a good chance he once played against both the Asheville team and the Greenville team.

My father also taught me how to play football. He taught me how to block, how to catch a football, how to tackle, how to throw a football, how a cornerback or safety should defend against a pass (“Keep the receiver in front of you!!!”), and how to run pass patterns. He also tried (unsuccessfully) to teach me how to drop-kick a football. He taught me that it is nearly impossible to stop the “pass/run option” at the goal line. He assured me that Doug Flutie was the best quarterback EVER.

In sum, he did his best to teach me what he knew best about the sports he excelled in as a young man. A time when he was a Cut Above the Rest.

He continued for the remainder of his life to be a Cut Above the Rest as a father…

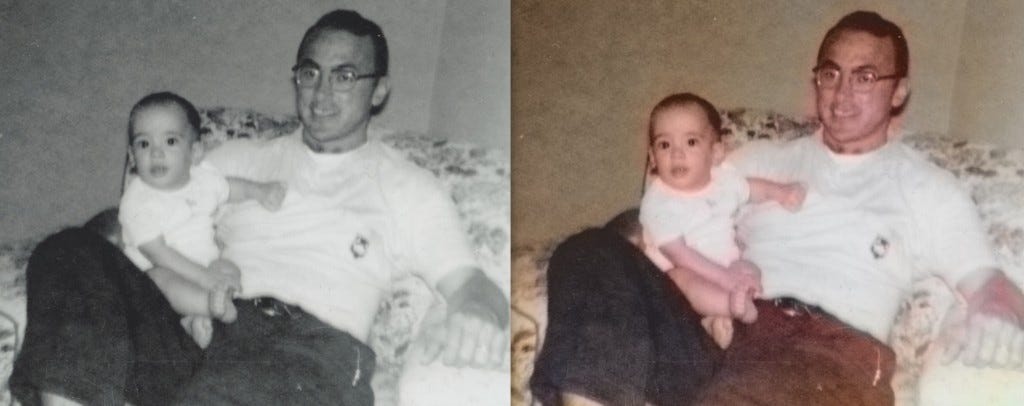

My father, Al Nozzi, holding me, Dominic Nozzi, on August 1960. I am six months old. My father is 29 years old.

I was fortunate to have been visiting him a little more than a week before he died and was able to tell him I loved him. He was a wonderful, spirited father and man who left a great legacy and great memories. Twice when I was visiting, he joined me in belting out the Dunmore Bucks war chant that he so proudly and memorably proclaimed throughout his life.

Cumma Veeva! Cumma Vyva! Cumma Veeva Vyva Vum!

Cumma 7! Cumma 11! Cumma rickety rackety shanty town!

Who can put ol’ Dunmore Down???

NOBODY! NOBODY! NOBODY!

If you have any interest in a hardcover book about my Dad, here is a link:

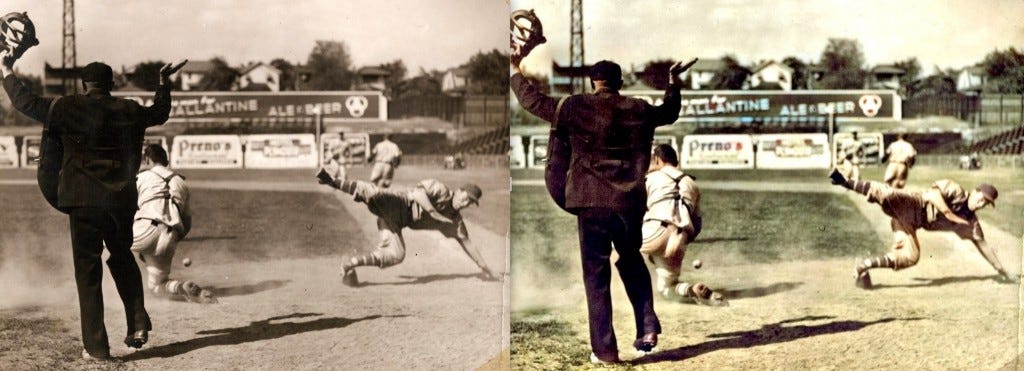

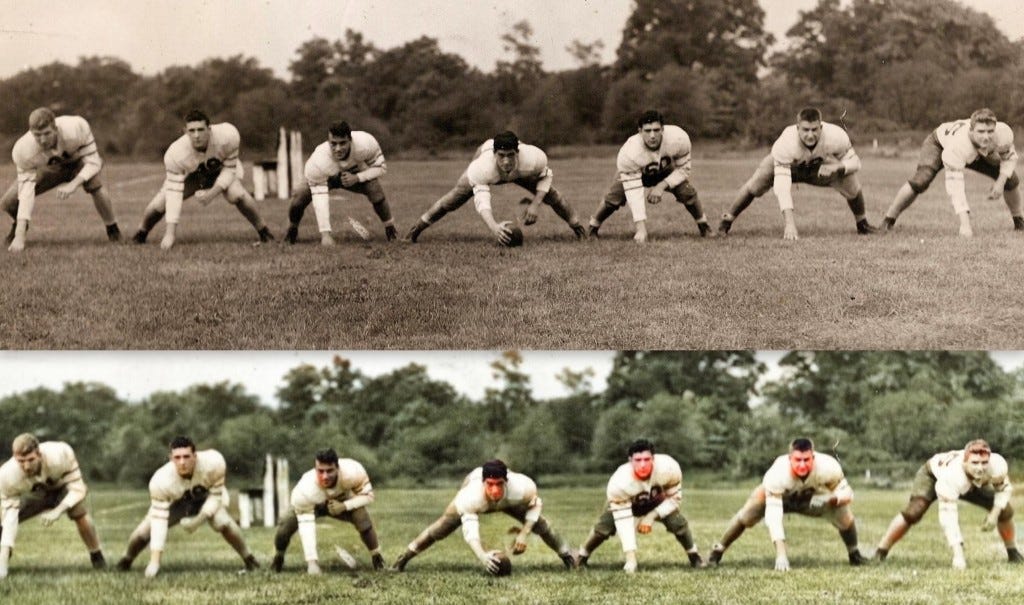

I colorized several old black and white photos of my Dad and the rest of the family here:

Nozzi and Lupia photos from 1910-1959.

Here are short videos of me and my Dad, seven years ago, singing a favorite Jimmie Rodgers song (“In the Jailhouse Now,” a song that was performed in the movie “O Brother, Where Art Thou?”):

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=OxTFnICqnvw

We also sang “The Women Make a Fool Out of Me,” by Rodgers:

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=0mMC9gEzRSo

His obituary, as prepared by my youngest brother Anthony.

A tribute video of Al Nozzi and his family.